Tasmania —

A Cash Flow Analysis

Based on a Working Paper commissioned by Ruth Forrest MLC and a presentation

to the Economics Society, Hobart, 22nd March 2012.

The aim of this

paper is an assessment of Tasmania’s past, current and forecast financial

position, over a 9 year period, from 2006/07 to 2014/15. In particular this

will include a close look at the General Government Sector’s (GGS) Cash Flow

Statements to

• Reclassify inflows and outflows into more

appropriate categories of ‘operating’, ‘investing’ and ‘financing’ as will

allow an easier interpretation of Government financial statements.

• Examine the components of each category of

inflow and outflow.

• Examine the source of inflows as Federal vs

State sourced revenue.

• Provide a basis for understanding and

measuring sustainability.

The General Government includes all

departments and agencies but not its subsidiaries, the GBE and State Owned

Corporations SOCs, which together with the GGS form the Total State Sector.

In simple terms, accrual accounting standards lead to 3 major financial statements for any accounting period: an Income (or P&L) Statement, a Statement of Financial Position (or Balance Sheet) and a Cash Flow Statement.

In simple terms, accrual accounting standards lead to 3 major financial statements for any accounting period: an Income (or P&L) Statement, a Statement of Financial Position (or Balance Sheet) and a Cash Flow Statement.

A Cash Flow Statement is the best guide as to

where cash comes from and how it is spent. It includes all receipts and

outlays, split between ‘operating’ flows which are mostly allocated to the

P&L and ‘investing’ and ‘financing’ flows which end up on the Balance

Sheet. Non cash amounts (eg depreciation) and accruals (amounts incurred but

not paid) are added to finalise a P&L and a Balance Sheet.

The non-cash ‘depreciation’ amount is readily

identifiable but the accrual amounts, principally the costs of unfunded defined

benefit (DB) superannuation are harder to locate.

The following table lists the accrued DB

superannuation amounts included in the P&L for the last 2 years. The

‘employer service cost’ is included in ‘superannuation’, ‘nominal

superannuation interest’ included as such and ‘accrual(gains)/losses’ included

as ‘movements in super liability’. All have been accrued; none have been paid

in cash. These amounts are shown at the foot of the table.

The cash amounts paid aren’t included in the

P&L as they simply reduce a liability accrued from a prior period. Instead

they are allocated to the Balance Sheet to reduce the unfunded superannuation

liability.

The operating profit figure or net operating

balance (NOB) as the GGS calls it is used to measure Budget sustainability, one

of the Government’s key fiscal strategies.

One problem with NOB as a measure of

sustainability has been that the capital stimulus grants from the Federal

Government (the Nation Building Grants) are included as income in the NOB

calculation although the ensuing capital outflow is not. This overstates

operating profits.

To allow for this the Government calculates an

Underlying NOB.

Nevertheless in her media release that

accompanied the recent Mid Years Report, the Treasurer referred to the

estimated NOB deficit of $246 million for this year rather than the underlying

NOB deficit of $387 million.

The NOB being a profit measure doesn’t include

amounts spent on capital items, so there’s a measure called the Fiscal Balance,

which essentially replaces the non cash depreciation amount in NOB with the net

expenditure on capital (in cash).

The Fiscal Balance is perhaps the most

accurate current measure of sustainability. It includes accrued expenses and

also capital outlays. In 2007/08 the Fiscal Surplus was $102 million and the

2008/09 Budget projected surpluses in each year of the Forward Estimates. In

the latest Forward Estimates the Fiscal Balance remains negative in each year,

in aggregate worsening by an alarming $318 million in the latest Mid Year

Financial Report. There was no mention of this in the Treasurer’s media

release.

The GGS is essentially a cash business and as

the Cash Flow Statement contains all inflows and outflows, not just operating

flows, it arguably is a better basis than NOB for beginning to understand the

sustainability and the operations of the GGS.

Having a surplus NOB suggests sustainability but

certainly doesn’t guarantee it. Businesses can appear profitable, with positive

profits, but they can be cash flow negative and non viable. The converse could

also be true. In the case of the General Government, surplus NOBs can disguise

negative cash flows because, for instance, of the extra needed for ’investing’

and ‘financing.’

Similarly having a Fiscal Surplus doesn’t

guarantee sustainability or viability either. ‘Investing‘ activities may suffer

in order to maintain a Fiscal Surplus, and this may have long term consequences

for the State with inadequate infrastructure for instance.

Continuing Fiscal Deficits will almost

certainly lead to an increase in financial liabilities as accrued expenses are

capitalised.

If and when Fiscal Surpluses (and NOB

surpluses for that matter) finally emerge it’s possible they will coincide with

cash deficits, when previously accrued or capitalised expenses are eventually

paid.

The above highlights the budgetary problems

confronting the State and the need for caution when using measures of

sustainability. The Government has acknowledged problems with too many measures

of sustainability and the latest Fiscal Strategy includes only one, the NOB,

with the aim of reducing “confusion and the potential to deliver mixed messages

about actual financial performance”.

To achieve an enhanced understanding of

sustainability a closer look at the components of inflows and outflows of

Government is needed and the best place to start is the Government’s Cash Flow

Statements.

The Auditor General (AG) in the last 2 years

has reported to Parliament a Cash Flow Statement, in a form contrary to the

strict Uniform Reporting requirements of Governments, but which reallocates

capital grants from the Australian Government as ‘investing’ cash inflows not

‘operating ‘ cash flows. The Cash Flow Statement reveals total cash received

and spent each year.

The numbers aren’t important at this stage,

it’s only intended to show the format of a cash flow statement, split into

operating, investing and financing cash flows and the components within each

category.

This paper will adopt the AG’s approach and

extend it a little further by reclassifying payment of benefits to retired

members of the State’s unfunded superannuation scheme as ‘financing’ outflows

rather than ‘operating’, because (notwithstanding literal interpretations of

accounting standards) that is what they are; they are a reduction in a liability

not an operating outflow in respect of current employees. The aim is to get a

more pragmatic classification of ‘operating’, ‘investing’ and ‘financing’ cash

flows.

How has the GFC affected the State’s cash

inflow? The blip in 2008 was, as we shall soon see, due to the Hobart Airport

sale. The peak was reached in 2011 with a flat line thereafter. Having endured

relentless descriptions of plummeting post GFC inflows, the total actual

inflows are surprisingly benign.

Let’s have a closer look at the components of

the cash flow, operating and investing. There is no inflow from financing

because no money has, or will be borrowed. Operating revenue includes general

and specific purpose grants from the Feds but not capital grants, and all our

own State source revenue, taxation, dividends from GBE/SOCs etc.

The operating revenue is relatively stable

showing modest increases over time. It’s the investing income that has provided

the volatility.

The steadily increasing operating inflows will

no doubt beg the question, how come we’re in so much trouble? Answer: The

operating outflows increased much faster as we shall soon see.

But first the rest of the inflows.

What comprises the investing income? 3 Items:

• Commonwealth Nation Building Grants

• Sale of non-financial assets such land buildings etc.

• Equity disposals, the Hobart Airport in 2008 and TOTE in 2012

• Sale of non-financial assets such land buildings etc.

• Equity disposals, the Hobart Airport in 2008 and TOTE in 2012

How has total State Government cash inflow been split between the contributions from the Australian Government and from our own sources?

The State’s share is simply the inverse of the Feds’ share. Over the last 4 years the State’s share has fallen as low as 36% but will climb back to 43% by 2015 mainly due to the withdrawal of the Nation Building funding. During the GFC and its immediate aftermath we relied on the Feds to bail us out. The general purpose grants via GST were less than expected but the Feds more than matched the falls with special purpose grants. Our own source cash fell. We can keep blaming the fall in Fed receipts for the cause of our current woes, but the simple fact is that it’s our own source cash that has lagged, not the Fed grants.

What are the components of State source

operating cash? Taxation makes up the majority fluctuating between 45% and 49%.

What comprises the remainder of State sourced revenue? Sales of goods and

services and returns from GBEs etc have both been cranked up in the 2012 to

offset reduced revenue from state taxation and interest.

What comprises State taxes? The largest contributor payroll tax is holding up with an increasing share of State taxes from 30% in 2008 to 34% in 2015. Over the same period duties will fall from 24% to 15%, a catastrophic fall. Other taxes have picked up the slack.

Of the ‘other taxes’ MV fees & registrations has steadily increased its % share and guarantee fees from GBEs/SOCs have been significantly raised whilst the remainder are stable in % terms or falling in the case of gambling receipts.

Now for the cash outflows. How has the pattern of cash outflows changed? It peaked in 2011 and the next 4 years will see small decreases. The Treasurer recently acknowledged excess spending in recent years, arguably represented by amounts above the black line.

But what are the components of the cash outflow, split between operating, investing and financing? The features to note are the rapidly increasing operating outflows which peaked in 2011 before pausing , declining then gradually increasing. Extra volatility is provided by changes to ‘investing’, mainly spending the Nation Building monies.

The increases and projected increases in operating outflows have slowed considerably since 2010 (the blue line). Had they continued the same trajectory as the years 2008 to 2010 it would have looked like this (the red line).

What is the breakup of operating expenses? In

% terms the components are quite stable. They may well move together. It’s

difficult to draw too many other conclusions from this limited data, whether

the % spent on wages is too high?

One salient observation from the above table is that the super expense is low. Given the level of employee entitlements it should be closer to 5% not 3%. This is because the costs of superannuation (the red Line) doesn’t include defined benefit DB members as the contributions are not set aside with cash. The cost of DB super accrued in the P&L statement (excluding actuarial movements) but not paid in cash plus the actual payments made in cash for retired members is shown in the next chart.

When pension and lump sum benefits are paid the Government includes them as operating outflows. Arguably, and this is what been done for the purposes of this paper, the outlays are ‘financing ‘ outflows because in effect what is occurring is a reduction in a liability incurred in a prior period, the unfunded superannuation liability, rather than an ‘operating’ outflow.

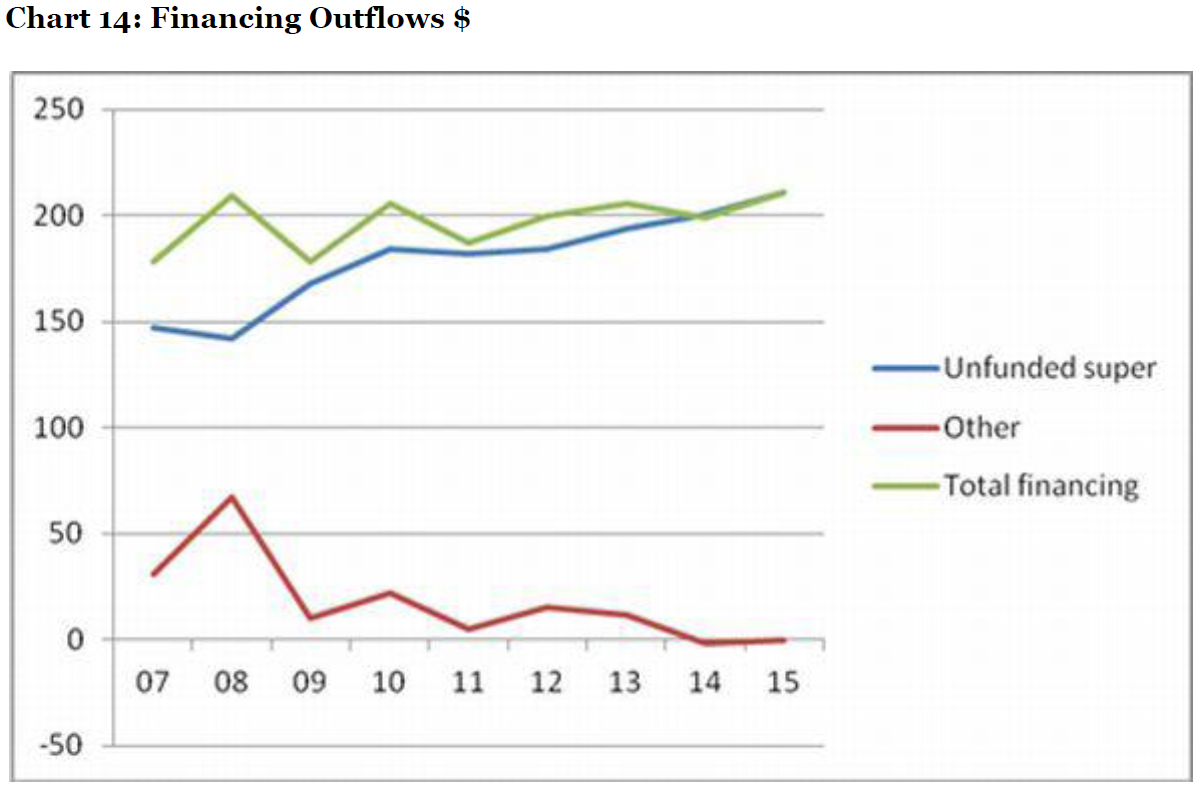

The ‘financing’ outflows are shown in the

following table. The red line shows repayments of the small amount of State

Government debt owing. The payments in regard to unfunded superannuation (the

pension and lump sum payment) are added to give the net outflow from financing

(green line).

What about investing outflows? The chart gives

the details, an increase up till 2011 followed by a decrease.

What is the breakup of investing outflows? The

majority is represented by purchases of non financial assets such as roads,

buildings infrastructure, plant and equipment. The remainder comprises equity

injections into GBEs and SOCs.

One of the Government’s fiscal strategies is to spend as much on new roads, buildings, plant etc as the existing ones are wearing out. In other words to ensure that the outlays exceed depreciation.

The following graph indicates that by 2015 outlays

will once again revert to the same as depreciation, similar to 2008. The

intervening years saw the years of Nation Building and additional

infrastructure outlays by the State Government. In real terms the outflow in

2015 is similar to 2008 (using CPI as a deflator).

Putting together the total inflows and outflows how does the cash balance track? The final year 2015 sees inflows exceeding outflows for the first time since 2008. It takes a long time to change course. This may be as much a reflection on the inertia of the system as any tardiness by policy makers—Newton’s First Law of Motion as it applies to Government finances.

The following graph shows the decline in cash (the blue bits). By 2015 the State will have only $333 million in cash. The cash balances can be a little misleading as the costs of superannuation for defined benefit DB members are not set aside in cash. Were the employer costs of DB super set aside each year (excluding interest on the unfunded amount) the cash balance would have been considerably worse, as shown by the red bits. Even if it were assumed that all employees were defined contribution employees requiring 9% of salaries to be set aside each month the result still shows declining cash balances becoming negative over the period of the Forward Estimates. This suggests the current structure is still flawed.

The Treasurer claims we are net debt free as

the blue bits in the following chart remain above zero. The unfunded

superannuation liability requires payment on a regular basis and forms part of

net financial liabilities (net debt plus the unfunded super liability).

The result, the red bits, in the following chart represents the Government’s net financial liability. Our liabilities are growing. The graph below tells the tale.

The result, the red bits, in the following chart represents the Government’s net financial liability. Our liabilities are growing. The graph below tells the tale.

Given stoic acceptance of flat line cash inflows (in nominal terms, worse in real terms), the following graph crystallises the State’s challenges on the spending side; falling total cash outlays, almost flat line operating outlays, declining investing outlays which will soon be exceeded by financing outlays.

Sustainable cash flow management arguably requires net operating cash flows to be sufficient to cover net investing and financing outflows. The latter are shown in the next chart.

The following chart shows net operating cash flows finally exceeding net flows from ‘investing’ and ‘financing’ in 2015. Sustainable?

The projections in 2015 may indicate sustainability as we finally achieve positive cash flow. However, it will need to be repeated for a good few years thereafter. But does it imply viability? A few observations:

• The forward estimates aren’t subject to

audit scrutiny. How accurate are they? In the past there have been significant

differences between forward estimates and actuals that finally eventuate. The

Government never tells us the assumptions used for future projections. They’re

simply handed down on a tablet as if from above. A cynic may be tempted to

suggest that it would be a foolish Government to produce a set a forward

estimates that didn’t contain a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel. The

latest Mid Year Report shows negative NOBs and Fiscal Balances all the way

through the Forward Estimates but just a sliver of light from a positive Cash

outcome in the final year. A precarious projection.

• How will ‘financing’ outlays move? Currently

they represent about 4% of cash outlays. Indications are as all DB members

retire in the next 20 years it may reach 6% to 7% of outlays. Thereafter the % will

gradually reduce to zero over a 35 year period as Members expire. (To sidetrack

a little, this suggests that we are in no way similar to Greece. The financing

liability is not a debt that has to repaid or rolled over at the end of a

certain term, and the costs to service whilst significant in $ terms, represent

only a small portion of total cash outlays).

• Are ‘investing’ outlays of 5% of cash

outlays in 2015 sufficient for our needs? Or will this % need to increase to

keep renewing and replacing buildings roads and infrastructure? The question of

GGS expenditure for ‘investing’ activities needs to be seen in the context of

all such expenditure amongst Governments, including that by the GBEs/SOCs and

local Government, because there will be varying economic and social impacts

depending on the type, an irrigation scheme vs a cycle path for instance, and a

coordinated approach will ensure a better outcome for each $ spent.

• Will the remaining funds for ‘operating’ be

enough to provide required Government services given flatline receipts?

The State’s dilemma is further compounded by

the fact that:

• Much of what has been appropriated into the

Special Deposit and Trust Fund (SDTF) in the Public Account has been

‘internally borrowed’ and spent.

• The majority of cash remaining belongs to an

account in SDTF termed Australian Government Funds Management Account which

contains Australian Government specific purpose grants awaiting expenditure. It

is not available to be spent on the State’s general purpose needs.

The Auditor General highlighted the problem in

his presentation to MPs in November 2011. The vertical columns represent what’s

been appropriated to SDTF, the majority being the straw (?) coloured portions

taken as hay from the barn, to paraphrase the Treasurer, or more accurately the

‘internal borrowings’ with the blue portions representing the remaining cash.

The red line is the untied cash, only $196 million at 30th June 2011.

Another interpretation of the above chart is

that Parliament has appropriated amounts to SDTF far in excess of the amount of

cash available, a puzzling approach likely to change if ever the Government

completes its review of the State’s Financial Management framework. The

difference between amounts appropriated to SDTF yet to be spent and the amount

of available cash is represented by the Temporary Debt Repayment Account which

indicates what has been ‘internally borrowed’.

The Government defence of the level of

‘internal borrowings’ was invariably to cite prudence. It would be imprudent to

borrow externally when internal funds are available. Quite true, especially

since repayments arrangements are very flexible, in recent years, non existent.

But the question should really be, why continue to appropriate funds into a

SDTF account as is happening with the Superannuation Provision Account (SPA) if

there’s no cash available? You don’t understand is the latest defence line,

it’s just a provision. A provision for what? A provision to provide for the

extinguishment of a provision (unfunded liability)? How about another provision

to reflect impairment, a provision for the estimated cash shortfall in regard

to SPA, just to turn add another layer of farce? Maybe not. That may be a de

facto acknowledgement that 100% cash backing for SPA is no longer possible

which implies that an account in SDTF may have been used for purposes other

than what it was intended, contrary to Sec 13 of the Public Account Act 1986?

The Government keeps topping up SPA with

further appropriations when there’s no cash, ostensibly with the aim of

eventually extinguishing the unfunded liability by 2035. But is there any point

if by 2035 the balance of SPA is simply represented by an equivalent sized

Temporary Debt Repayment Account representing all the ‘internal borrowings’?

On present indications that is what is likely

to happen, although the Government still refers to “short term issues with cash

backing”. The SPA account as set out in Budget Paper No 1 comes with the

explanation that “there are sufficient receipts from agencies, the Reserved by

Law contribution and from interest on the SPA balance to meet the emerging

costs” which leaves one with the distinct impression that we are dealing with

cash amounts. This is not the case. They are just appropriations. Even the interest

credited to SPA ($81 million expected in 2012) is an appropriation, a book

entry, not interest earnings per se as is generally understood by most readers.

The actual expected interest to be earned by the total GGS is only $23 million

for 2012.

Maybe it would be preferable to admit to the

improbability if not impossibility of the task of trying to extinguish the

unfunded liability by a certain date, thereby reducing the misunderstanding in

the community, and treat payments for DB pension and lump sums, in a more

transparent and realistic manner as ‘financing’ outflows which reduces a

financial liability, as has been done for the purpose of this paper.

Most of the confusion surrounding the system

of internal borrowings and cash backing stems from the dual fund Public

Account: a Consolidated Fund and the Special Deposits and Trust Fund. The

former is where most amounts are first received. Funds are then spent as

Reserved by Law amounts or amounts appropriated by Parliament. Parliament will

also appropriate amounts to top up balances in SDTF which consists of various

working accounts, deposits and trust funds. The problem now is, as highlighted

in the previous chart, is that for every $4 that has been appropriated by

Parliament there is only $1 in cash available. If one excludes the specific

purpose grants from the Australian Government the figure is $1 cash for every

$10 appropriated. The ‘missing’ funds from the Public Account are reflected in

the Temporary Debt Repayment Account. The opening balance of this account when

the old cash accounting system was replaced with the more standard accruals

system about 10 years ago was $700 million represented by maturing debt that

had been repaid by sensibly using cash balances in other accounts, in other

words by ‘internal borrowings’. But it has been the last few years particularly

2011 which has seen such a massive blow out in ‘internal borrowings’, none of

which relate to repaying maturing debt but rather to helping fund the ordinary

operations of Government. The dual Fund Public Account system is looking a

trifle anachronistic. Maybe it’s time to go to a single Fund system as proposed

by Treasury some 2 years ago, and start confining appropriations to available

cash, which incidentally will include cash from borrowings if ever that happens

in the future, and which may be understandable by a wider number of

stakeholders.

In summary the State’s current situation

manifests as follows:

• Flat line cash inflows in nominal terms,

worse in real terms.

• A reluctance to address the matter of

reduced inflows.

• Flat line ‘operating’ cash outflows.

• Falling ‘investing’ outflows, to such an

extent that expenditure on new capital will barely cover impairment of existing

capital by the end of the forward estimates period.

• A small but inexorably growing ‘financing’

cost of unfunded superannuation which will soon equal amounts spent on

‘investing’, on new capital in other words.

• A maintenance of the fiction of ‘net debt

free status’ when our financial liabilities are still increasing.

• A growing reliance on cash in advance from

Federal specific purpose grants to finance the general operations of

Government.

• The borrowing and spending of amounts

appropriated to SDTF without any reasonable chance of repayment.

• An absence of any realistic measures to

assess the long term viability of the State.

All measures of sustainability—-underlying

NOB, Fiscal Balance and even Cash Balances can be misleading from time to time,

so it is important to understand the components that affect the measures. Cash

Flow Statements gives a realistic view of the operations of Government. Most

people understand cash inflows and outflows. The different activities of

‘operating’, ‘investing’ and ‘financial’ when explained are not difficult to

grasp.

To date there has been a conspicuous failure

by Government to give an adequate and coherent explanation of our budgetary

problems. To its credit the Opposition prepared an ‘alternative’ Budget this

year, but that too didn’t appear to grasp the problems ahead and the tinkering

suggested would have negligible effect (if any) on the State’s battle to find a

sustainable path.

A greater understanding is a prerequisite for

moving forward. A little more collaboration across the spectrum would assist.

Arguably for a start, ‘financing’ outflows and targets for net ‘investing’

outflows need to be tabled for all to understand and then ‘operating’ flows

designed to cover both with a cash buffer for a rainy day.

We certainly can’t rule out a few of the

latter.

Postscript

The Secretary of the Federal Treasury Martin

Parkinson recently gave a speech http://www.treasury.gov.au/documents/2340/PDF/AICC_charts_final.pdf in which he made a few points pertinent to the above

discussion.

He said ”.... the task of maintaining

medium-term sustainability for both the Commonwealth and the States has been

made harder by developments in the revenue base. Indeed, for both levels of

government, surpluses are likely to remain at best razor-thin without

deliberate efforts to significantly increase revenue or reduce expenditure.

This predominantly reflects the sharp

weakening of revenue collections over recent years.

the task of maintaining medium-term

sustainability for both the Commonwealth and the States has been made harder by

developments in the revenue base. Indeed, for both levels of government,

surpluses are likely to remain at best razor-thin without deliberate efforts to

significantly increase revenue or reduce expenditure.

This predominantly reflects the sharp

weakening of revenue collections over recent years.

The tax-to-GDP ratio has fallen by 4

percentage points since the GFC, and is not expected to recover to its

pre-crisis level for many years to come. This reflects a combination of

cyclical and structural factors”.

Endnotes

1. The focus on the cash flow statement in no

way is intended to imply that the old cash system of reporting by Governments

is superior to the accruals system. The accruals system is fundamental to

reporting on the stewardship of public assets and liabilities. Nor is it

implied that the cash flow statement should be the sole guide for public policy

makers. It is recognised that financial statements as produced by Governments

are predominantly to satisfy is statutory obligations. The intent of the paper

is to adapt the cash flow statement to provide an easier and more meaningful

interpretation of financial statements for lay users. Tasmania raises less of its

own revenue than other States and is more of a ‘price taker’. It is basically a

small service provider. It doesn’t have huge service responsibilities as the

Australian Government does with defence and social security, for example. It

has an extremely limited fiscal role (if any) and a limited ability to borrow

to fund deficits. An examination of its cash flows provides the best way of

diagnosing its financial health. Profitability and rates of return on assets

are not of paramount importance in the public sector being immaterial compared

to sustainable and viable cash flows.

2. Sustainability is not defined by the

Government. The common usage definition is assumed. Viability is assumed to be

a subset of sustainability, with higher benchmarks. In both cases the precise

definitions are not crucial for the purposes of the paper.

3. The inclusions of equity disposals as own

source revenue is not intended to endorse such disposals as a means of

achieving sustainability. Any discussion about sustainable cash flows should

obviously exclude the one off boosts provided by equity disposals.

Data Sources

Treasurer’s Annual Financial Reports, 2007/08,

2008/09, 2009/10 and 2010/11.

Analysis of the Treasurer’s Annual Financial Report 2010/11, Report of the Auditor General.

Tasmanian Budgets 2011/12 and 2008/09, Budget Paper No.1.

2011/12 Mid Year Financial Report.

Hansard, Legislative Council, Answer to Question Upon Notice, 21st Nov 2011.

Analysis of the Treasurer’s Annual Financial Report 2010/11, Report of the Auditor General.

Tasmanian Budgets 2011/12 and 2008/09, Budget Paper No.1.

2011/12 Mid Year Financial Report.

Hansard, Legislative Council, Answer to Question Upon Notice, 21st Nov 2011.

No comments:

Post a Comment